Grant Morrison and Gerard Way provide insight on the great potential of the comic form, their creative relationship, and ‘the golden age of Australian superheroes’.

The singer says he feared his daughter might have ended up without a father

Gerard Way has revealed he relapsed into alcoholism after his former band My Chemical Romance released what would be their final album.

The singer, who will release his debut solo album ‘Hesitant Alien’ on September 29, opens up in this week’s NME about how he fell into the self-destructive habits of his 20s shortly after the release of My Chemical Romance’s 2010 LP ‘Danger Days’. He broke up the band, he says, to save himself.

“I relapsed, not into drugs but booze,” he says. “I was self-medicating again to get through, and I’d forgotten how miserable that made me. It took me to the dark place again, but there was more at stake this time. I started to face the hypothetical reality of [daughter] Bandit not having a father. I started taking that seriously, thinking, ‘I want her to have a dad. A guy that’s present. Because one way or another – either by death or by asylum, she’s gonna be fatherless if I keep this up.’”

The choice, he says, was an easy one: “Break the band or break me.”

Earlier this week, Way announced that he will play his first ever solo gig to just 400 fans at Portsmouth Wedgewood Rooms on Wednesday night (August 20). He will also perform at Reading & Leeds Festivals this coming weekend (August 22-24).

Watch the video for Way’s new song ‘No Shows’ below now.

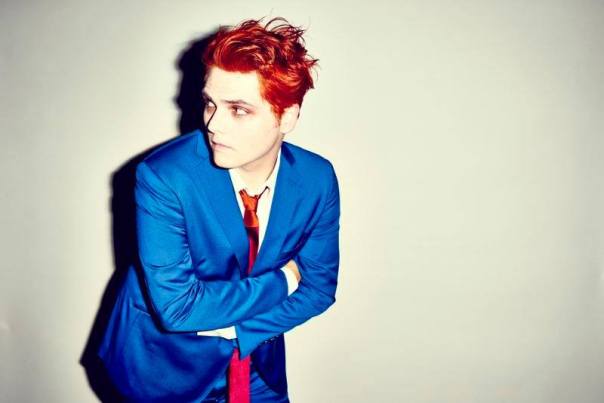

As the frontman of My Chemical Romance, Gerard Way seemed to have it all. The next chapter requires something altogether riskier.

It all began with a guitar. My Chemical Romance first came to life when the band’s frontman, their leader-in-waiting, picked up a 90s Fender Mexican Stratocaster in his parents’ basement and wrote their very first song. Twelve years on, as the band were finally drawing to a close, it was that same Lake Placid Blue guitar that Gerard Way turned to.

It’s safe to say that Gerard was stepping into the unknown. For the best part of a decade-and-a-half, he had graced stages around the world, kicking and screaming, sweating and bleeding his way to the most dizzying heights of popularity. He had taken his band out of the dirty basements of New Jersey, tracked down the souls of 1000 evil men, led a deathly army and become his very own superhero. With each of their albums came a new era for the band, and with every new concept, legions of fans would follow. Then, one day, My Chemical Romance became just too big a monster.

“It had,” agrees Gerard. Sat in the basement of a central London hotel, he looks a little different to the last time he was on UK soil. One of the last great accolades of the band saw them headline Reading & Leeds Festival just over three years ago, but gone is the flame red hair and leather jacket that he boasted during their ‘Danger Days’ performance. He’s traded it in for a messy mound of blond locks (for the time being, at least), blue jeans and some beaten up Converse. He looks relaxed, ready for things to set in motion once again, unafraid to admit that the next part of his life began at the end of his last. “There was a large part of me that wanted to escape that bigness, which I came to terms with over time. I learned to accept that it had grown to that and to love it for what it was, despite how big it had gotten. I came to peace with that part, but at the beginning of the break up, for sure, I was trying to escape this largeness.”

By the time the band called it a day back in March 2013, they had sold over four million albums worldwide, climbed to the top of the charts and headlined festivals on both side of the Atlantic. Their incendiary brand of punk rock – visceral but somehow eloquent, morbid yet enamouring – proudly blurred the lines of niche and mainstream, all the while taunting critics with its moments of bombast and flair. With the release of their third album ‘The Black Parade’ they had grown bigger than ever; they felt unstoppable, a force to be reckoned with in their gothic military uniforms, but when touring drew to a close in 2008, that couldn’t have been further from the truth. “I don’t know how much of a secret this is,” offers Gerard, “and I don’t think it is, but when we finished ‘…Parade’ and we had finished the touring, I didn’t want to do it anymore. That was a nice ending point for me. It was an extremely high note, I had said all I’d wanted to say. There was nothing more for me to say under that umbrella of My Chemical Romance.”

Somewhere along the way, his priorities had changed. With the band growing up and beginning to settle down with their wives and children, he had bigger responsibilities than his own artistic urges. As the project grew, drawing more and more people into the mix, there were less opportunities to walk away, and more depending on him than ever before. “You know, you try to be responsible,” he explains. “You’re becoming an adult and so you think one of those things is, ‘Well, I’m gonna be responsible. We’ve all got mortgages and families now and the right thing to do is to stay in this.’ Then you start thinking about the crew that you help; they work with you and that’s how they make their pay cheque. It gets bigger and bigger. It becomes that machine and then you don’t want to turn your back on anybody, not a single person. So, you go against yourself, you go against what feels right, to ‘be an adult’.”

Having closed the door on ‘The Black Parade’ almost six years ago now, things soon became quiet in the MCR camp. The band – guitarists Frank Iero and Ray Toro, along with Gerard’s bassist brother Mikey – spent time being husbands and fathers, settling in to that new period of their lives. That was until September 2010 at least, when the notoriously catchy, gloriously cartoony trailer for ‘Na Na Na (Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na)’ burst onto the internet. The band were back, reborn as superhero rogues in a post-apocalyptic land, another concept album firmly in their grasp and another touring schedule spanning way out into the future.

“As a human being you have to understand and deal with the process, not just run away from it,” Gerard reflects. “I wasn’t running away from the bigness, but I wasn’t happy doing it anymore, and it’s not what I wanted for my life anymore. It’s not the kind of father I wanted to be, or husband, or artist for that matter. It’s not who I wanted to be any longer. To go against what your inner-self is telling you – to go against the art like that – and keep grinding it and keep trying to milk it and make it work – not the guys, but me personally – that didn’t feel right. So, everything from the end of ‘…Parade’ to the end of the band just felt like I wasn’t being honest with myself. It was doing serious damage physically and mentally over that time.”

It took the release of fourth album ‘Danger Days: The True Lives Of The Fabulous Killjoys’, their consequential 7” collection ‘Conventional Weapons’, and a performance at New Jersey’s Asbury Park to shake Gerard into action. It admittedly took a while to sink in – as he later went on to explain in a closing letter to fans – but soon enough, he knew that their time was up. “You know,” he muses, “I think being an adult is not necessarily running away from things, but it’s doing exactly what you’re supposed to be doing. You have to be honest with yourself. I think that’s how you end up with a lot of really unhappy parents, who raise unhappy children that don’t want to be around them. I’d rather make a quarter of what I made in MCR and have [his daughter] Bandit grow up and say, ‘My dad was awesome. He had a great time making art. He loved life, he loved looking at life through a lens, he taught me how to look at life.’ I would much prefer that to, ‘Yeah, I kinda see my dad. He drives a Porsche, he doesn’t talk a lot. He’s on the computer a lot. Sometimes he writes comics but not really.’ I was just so unhappy with where I was at, that’s the way it started to become.”

It was time for Gerard to pick himself back up again. With the band laid to rest and his mind finally at ease, he was able to turn to that guitar – the same one he had written ‘Skylines and Turnstiles’ on twelve years previously, the same one he had introduced in his closing letter to fans – and start over.

“I knew I would,” he states, without a flicker of hesitation. “I just didn’t know what it was going to be.” At first, the frontman had set his sights on forming a new band. Immediately inspired, he “started cooking up art, and trying to visualise the kind of instruments” they would need. It grew more and more ambitious as his imagination ran wild. “I realised, you’ve gotta take ownership over yourself. You’re not gonna start a band because that’s not gonna work out for you. You’re pretty uncompromising so don’t put yourself in a position that’s based on compromise anymore.”

The birth of Gerard Way’s solo career was as simple as that. It was an opportunity for him to explore the paths untrodden by his former project, all the while looking at things through a different pair of eyes. He didn’t even have a concept in mind, for starters. “When it became a solo thing…” he pauses to think. “Visually there’s a concept but there’s nothing that’s a concept about the album. That’s the first time I’ve ever attempted that; it’s not a concept album at all. It’s nice; it’s a lot more varied because of that. I know My Chemical Romance was very varied, but this feels more so.

“A lot of it was completely blind flying and I loved it,” he enthuses. “It was extremely free. It was sitting with a guitar at a mic and just hitting record, and being like, ‘Alright, let’s hear it back. Okay, let’s do this.’ The opening track of the record was literally just me grabbing my brother’s bass, because it happened to be there, and just playing and building off that. I would do that, and then I’d say, ‘Okay, I’ll take the guitar now. Open me a new track.’ There was just layering and layering and layering and then we’d say, ‘Let’s get some drums on.’ It was really free. It was just grabbing stuff.”

Not only was it the first real chance for Gerard to be behind the guitar on an album – “when you’re in a band with two really amazing guitar players, you feel weird to wanna play guitar” – it also presented him with the freedom to roam his own, more personal influences for inspiration. “I got to go extremely deep. I knew that if I wanted to make a song that was going to sound like The Jesus and Mary Chain, it could really go that far. When you’re in a band, everybody has a fingerprint and that’s what makes that band special. When it’s just your singular fingerprint on it, you find that you can go deeper with it.” While My Chemical Romance had lurked at the heavier realms of his tastes – from Iron Maiden to Misfits – his new album became a place to explore. “[It has] everything from shoegaze to Britpop, and it’s a very British album. Everything from fuzz rock to noise rock, to experimentation, to Berlin-era Bowie and Iggy stuff. I’ve distilled it into some other thing, and there’s a thread of that throughout the record, but I went deep into my influences.”

Writing the album, dubbed ‘Hesitant Alien’, also allowed for the former frontman to gain his own sense of closure. Having spent over a decade in a band as notorious as My Chemical Romance had become – no one’s forgetting their infamous dalliance with the British tabloids any time soon – the time away, and the songs he wrote, saw Gerard face up to his own personal dilemma: re-discovering his place in the musical landscape. “Definitely each song is its own thing this time. They’re all connected by a sense of alienation and the idea that figuring out where I fit into music was realising that I don’t exactly fit into music, and that’s kinda how I fit.” He laughs, “that’s my role; my role is to be myself and super-unique and not worry about how I fit in. Not in an outsider, rebellious way, but in a celebratory way, saying ‘I’m different, this is what I do, and there’s nobody that does this like I do it, so I’m gonna be the best me I can be.’”

That’s not to say that Gerard believes it’s plain sailing ahead. There’s always the fear of the new, fear of the unknown, of what could come next. That’s something he’s having to face head on. “Yeah, there’s a fear attached to it,” he agrees. “You have nobody to turn to and say, ‘Is this any good?’ You have nobody to turn to and say, ‘Do I look alright?’ That’s all gone, so you have to really believe in yourself. There’s a good fear that comes with it and there’s a bad fear, and that’s the unknown: ‘Is it gonna work? Are people gonna like it? What am I doing? Why did I do this?’ All that bad stuff, it creeps in!” he laughs. “It comes from a place of fear. Everything that’s the right thing to do is extremely hard. It should be fun, but it should be the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do, next to having My Chemical Romance break up.”

There’s also the question of his future audience. With My Chemical Romance fans ready and waiting for new music, there’s no shortage of people who’ll undoubtedly give the record a listen, but who is it that’ll stick around? Have their tastes grown to match his, or will they move quickly on? More pressingly, who from outside those boundaries might raise an eyebrow for the ex-frontman of a band who were stuck with a label that’s been more than difficult to shake: who exactly is going to care? “I think I’d like to reach…” he begins, before pausing. “Uhh, it’s weird. I don’t want to…” he trails off, before starting afresh. “I really respect the My Chem fans so it would be nice to carry on the journey with them, but I think it’s gonna go how everything else goes. You’re gonna have a group that likes it, a group that doesn’t like it, and a group that’s very indifferent to it. I do think that because of the influences of the record, maybe some of the sophistication of it, it will appeal to people maybe closer to my age, or in their early 30s at least.

“I know I would listen to this record, and that’s not to say I wouldn’t listen to My Chem records, but My Chem was very different. When we did something in My Chem, it was all gut and psychology. This time, with this album, I was very conscious in my influences and I chased them down very hard. I started to make the record that I wanted to hear, that I wanted to go into a store and buy. It was important for me to bring fuzz pedals back into music. I had a mission this time and it was a sonic one. My Chem had a very socially-driven mission, and now this was, ‘No, I’m gonna get fuzz pedals on the radio. That’s my goal.’ I think audiophiles will like the record a bit more. We got Tchad Blake to mix it; people who are really into mixing will know Tchad’s work very well. Then, Doug [McKean, the album’s producer] and I experimented so much with the tones, so I think people that maybe didn’t like My Chem would like this…

“I think it’ll get a fair shake,” he concludes. “What they feel about it after they’ve listened to it, I won’t know, but I definitely feel like somebody will go, ‘Alright, well I’ll try this dude out and see how it goes.’”

As for the reaction he hopes the album might provoke, it seems to be the mantra that he himself is trying to follow. “I just hope they take away that…” he pauses one last time. “Just to be free, and just to do what you’re feeling, to not over think it. To take the risk, and do the hard things.”

Over the past three years, Epiphone.com has had a running conversation with Frank Iero, inventor of the Phant-o-matic Wilshire and co-lead guitarist with pop sensation My Chemical Romance. When MCR broke up in early 2013, Frank granted us one of his first interviews and we’ve been along for the ride as he stepped back, re-grouped, and began making music again. Frank popped in to see us during NAMM and offered Epiphone and many of our friends around the world a sneak peak at his new album Stomachaches. And of course, we sat down with Frank before the show to talk shop about guitars and the mysterious ways of the music muse.

——————–

When we last spoke with you, My Chemical Romance had disbanded and you were working on some music at a very casual pace. Now things are picking up in a big way. What’s your life like right now?

You know, it’s crazy. I feel like if we had talked maybe… 4 months ago, I would have said: ‘Ok I have some down time on my hands. I’m enjoying the free time. I’m getting ready to pick things up.’ And now it’s so hectic, I can’t even breath (laughs)! It’s kind of nuts. Which is fun. I like being busy.

Did you miss that feeling? With My Chemical Romance, you kept a very busy pace. Physically, you must have been used to that. Is it good to have that energy back?

Did you miss that feeling? With My Chemical Romance, you kept a very busy pace. Physically, you must have been used to that. Is it good to have that energy back?

It is welcome but it’s a very different kind of busy. Mainly because I don’t have other people to rely on. Nobody else is picking up any kind of slack. And if things fall by the wayside, it’s all on me. If things go well, it’s all on me as well.

That must be pretty energizing, too since that gives you some more opportunities to be creative.

It does. I guess the concern there–or the juggling act–is not to let the craziness of the business-side seep into the creative. Because things will come your way and sound like really great opportunities and I always say ‘yes’ if it’s something I want to do. But I never think: ‘Oh my God! How am I going to pull this off?’

So what happened in those four months? What changed your answer from ‘I’ve got some downtime’ to ‘I’ve got a new record?’

I started out–well, I didn’t think I was writing a record. I was at a point where I was kind of beside myself with the way I felt physically. I just had these horrendous stomach aches–I battle with nausea, basically. But it had gotten where it was really coming to a head. It was sucking the life out of me.

So in order to kind of like–in a defiant way–reclaim my life back, my creative life back–I forced myself to do something to get my mind off of how I was feeling. And once again–like it did when I was young–music saved me. And I just started writing constantly and going down and demo-ing and recording. Slowly but surely, I realized I had this group of songs and I guess I had written a record. It was this weird reveal to myself. The funky thing about it is there are themes I feel run through that record but it’s very diverse musically–almost to a point disjointed–because it wasn’t ever thought to be a record. I like that janky feel to it.

Is there a theme or a thread to the new songs you’re writing now?

There are certain things I’ve always been fascinated with as a writer and as a person. The power in frailty–the beauty in the things that most people find mundane. Or even the things that some people are scared of. There’s a kind of purity that I see in these things, if take the time to look at them a different way. And the other theme that I feel runs through the album is this search for calm or peace of mind. A place where you can feel like you belong. At least in my experience we’re all searching for that. It’s kind of that life journey: what does it all mean? Where is my place in all of this? Where can I feel like I have finally found my point of existence, where I can finally feel safe.

Do you feel like you’re at that point as a writer because you’ve had such a big change in your lifestyle in terms of being at home and not on the road. Do you hear a different writing voice coming through?

You know–absolutely there’s a different writing voice come through. There is something to be said about coming home and having that down time. Because, you tend to have a hard time relating to real life again. When you finally come back down to Earth, it’s difficult to find your speed, so-to-speak. So there is something about that. But I feel like when I started writing songs and they started coming out of me, I had been off the road for awhile. Anything you go through changes the way you are now. And I had a lot of huge life experiences in a short amount of time. I came home off the road and I had three children. If that doesn’t change you then there’s something wrong (laughs)! But there’s definitely something to be said for a different outlook. I can’t imagine what the next stage brings.

Tell us more about your new record.

Tell us more about your new record.

The title of the new record is extremely literal. It’s called Stomachaches and that’s for a reason. Because I kind of felt like the spark for this creativity, the seeds of these songs, started as these horrendous stomach aches. So I could have called it “12 Songs” or “12 Stomach Aches” (laughs). They are near synonymous with each other.

Did you write most of the songs on your Epiphone Phant-o-matic?

A lot of the songs stem from me playing bass. And I don’t know why. I have no good reason.

Now you have to design an Epiphone bass.

Yes, I would like that. I feel like the foundation of the melody and chord changes were written on bass. There are a lot of bass lines driving the songs on the record. Guitar on this record was another voice. And I think that’s something that I’ve always done with guitar lines that I write. Even with my past band, My Chem, I would come in and I would ride that space between vocal and rhythms. I tried to weave in and out of supporting those melodies. That’s something I’ve always loved to do. And on this record, I feel like the guitars are at times very dirty and squashed and it’s almost like a yell coming through.

Jarod Alexander played drums and you played all the other instruments. So when you went into the studio, did you track with bass and drums?

What we did was… well, you know there’s the correct way of doing things? That was not how it went! A lot of the demo-ing was me doing all the instrumentation and programming drums. And then I brought them to him. There’s a song on the record called “Blood Infections” that is basically almost all bass. It drives the entire song. So that one I did track with bass and Jarod. But then there are some songs like “She’s the Prettiest Girl at the Party and She Can Prove It With A Solid Right Hook” where I ended up using a lot of the original demo guitars. The way I recorded them was so integral that I couldn’t recreate it. So I thought, why try to mimic something that happened just in a moment in time. Now it’s done. It’s at the pressing plant. I got the test presses before I came to Nashville.

What kind of touring do you have planned?

So far, we’re booked for the U.S. We start in September. For the most part it’s supporting Taking Back Sunday and The Used. And then I would say we’re hopefully going to the UK in November. We’ll see what happens after the holidays.

When you’re touring as support, you have a chance to surprise the audience and it’s also a very confined set. Do you like that idea? And you can go out to dinner afterwards instead of waiting until late.

I do like that! For me, I requested a support slot. I wanted to take our time and really become a band. The funny thing about making this record was that I did it by myself. So these songs will live with a band for the first time. The rehearsals for this tour are the first time I’ve had a chance to perform these songs.

Do you want to tell the bass player what parts to play?

Well funny enough, I asked friend Rob to play bass who is usually a guitar player. The bass lines were so important and so weird I thought that to get the parts played incorrectly (laughs) the way I did it, I needed to get a guitar player since I play bass like a guitar player.

This is a very personal record. Do you feel like you can tell the band to let go or do you want to try to recreate the record on stage?

You’re right. I had a very intimate experience with that record. Those were late nights with just me pining over things. These stories that I wanted to tell. As far as the stage show, in no project that I’ve ever been a part of have I wanted to recreate the record live. I feel like the live experience should be a totally different animal. It’s like book to movie. If you want to listen to the record then you have to stay home and listen to the record!

NME speaks to Gerard Way about his upcoming Britpop-influenced solo album, life after MCR and why he’s chosen Reading and Leeds to debut his new music.

Mikey Way began planning Electric Century long before My Chemical Romance hit it big, he just didn’t have the means to pull it off … mostly because he was 12.

“I was in my seventh-grade science class, and I wrote ‘Electric Century’ on a notebook, and I was like ‘I want to do this band,'” he told MTV News. “And right then I began filing away the kind of music I wanted it to be: Britpop, the party influence of bands like the Happy Mondays, New Order, Public Image Ltd. It was always something I wanted to do.”

And now, with MCR officially over, he’s finally (re)turning his attention to the project, teaming with David Debiak (Sleep Station, New London Fire) to make Electric Century a reality. The band was formally unveiled Wednesday, when Way’s image graced Alternative Press’ “100 Bands You Need To Know” issue, and since then, things have hit hyperspeed (EC is still so new that they don’t have an official press image).

But that’s fine with Way and Debiak … after all, they’ve been waiting for this moment for a while.

“We were supposed to have a little break after [My Chem’s 2006 album]The Black Parade, and I was like ‘Dave, me and you should really get together and start writing stuff,'” Way explained. “But unfortunately, we jumped right into another album after Black Parade, so we didn’t have a chance to do it … but we talked about it a lot.. And that basically continued for about four years. I told Dave ‘I don’t know when it’s going to happen, but it’s going to happen.'”

“Mikey would send me an annoying amount of voice memos, just little musical ideas, and I’d listen to, I don’t know, a countless amount of them before something stuck,” Debiak added. “I’d start writing lyrics based on those ideas, until eventually, about a year-and-a-half ago, we had time to make this happen. Since then, we’ve written about 35 songs, and right now, our entire focus is finishing a full-length album.”

Debiak handled the lyrics, and Way wrote the majority of the music — “I’m doing a little bit of everything; guitar, keyboards, background vocals,” he explained — and slowly, Electric Century began taking shape. There’s a full lineup being assembled as you read this (Debiak assured me fans will learn the full lineup very soon), and the duo plan on meeting with potential labels in the next few weeks … which means that, after nearly 20 years, Way’s fantasy band will finally become a reality. And, after spending a decade shying away from the spotlight as MCR’s bassist, he’s ready to step to the forefront with Electric Century.

“You know, on the day I showed up for the AP shoot, I was like ‘Where are the rest of the dudes?’ It was kind of like jumping into the ocean, like, ‘Here goes,'” Way said. “When I started in My Chem, it was no secret that I had bad anxiety and depression and drug issues, but then, starting with Black Parade, there was a sea change, and I broke out of my shell. And it led me to this point, where I’m ready to take charge now. It took me years to get here, but I know I’m ready.”

And to that point, Way knows that there are some My Chemical Romance fans that will probably never give his new band a chance. Shoot, some are still holding out hopes for a reunion. But he’s not concerned with the past … rather, with Electric Century, he’s embracing the future.

“When people first used the term ‘Electric Century,’ it represented the shift from steam power to electricity, and it changed the entire universe. And, for me, this is a complete change in my life, on many levels,” he said. “No matter what, throughout time, whenever somebody who was in a popular band goes to another band, there’s people that unconditionally love it, and there’s people who unconditionally hate it without listening to it … you’ve just gotta take it on the chin, and do what’s right, and write the best possible songs.hat point, Way knows that there are some My Chemical Romance fans that will probably never give his new band a chance. Shoot, some are still holding out hopes for a reunion. But he’s not concerned with the past … rather, with Electric Century, he’s embracing the future.

“As far as people saying ‘It’s too soon, My Chem just broke up,’ it’s like, ‘No, it’s just done,” he continued. “We’ve been formulating this in a laboratory for like four years now. We’ve written 35 songs. It’s time to do it.”

via

Frank Iero has done a little bit of everything in the music industry. Perhaps best known as the rhythm guitarist for My Chemical Romance, he’s also fronted bands like LeATHERMOUTH and Death Spells, and worked on original material for soundtracks. Before all of that, he was a member of Pencey Prep, perhaps one of the paradigm examples of contemporary garage punk.

In December, Iero set up shop with B.CALM PRESS, releasing an EP of covers called for jamia… Earlier this month, Iero took some time via e-mail to share the B.CALM origin story and his thoughts on DIY with Velociriot.

Velociriot: I know you’ve talked about this before, but what is B.CALM? Where did the inspiration for it come from? Where did the name come from?

Frank Iero: B.CALM is an entity under which I can release the different things that I make. Instead of finding a label and a publisher and a merch company and a fine art distributor, etc, etc, for all of my different outlets, I just decided to start my own thing, from which I can independently release certain projects under one umbrella. So far we have done music and merchandise and I would like to expand that into the other mediums I feel creative in, but it’s an extremely small operation and a lot of work.

The name B.CALM stems from the nature of the company I wanted to make. It’s intimate and pure, very hands on and personal to me. A place where I can release the things that I hold dear, a sanctuary for my art. It’s an acronym of sorts…possibly more of a letter jumble. I wanted the name to really mean something so used my children’s initials, LB CB MA, and formed a statement I needed to hear.

V: B.CALM seems like it has been a pretty personal project for you – do you see it continuing to be a place for personal pieces, like for jamia…?

FI: Yes absolutely. I’m not saying I will never release things that I make anywhere else, but I wanted a place to have absolute control to do the things I’ve always wanted to do, the way I wanted to do them. I think of B.CALM as a home base of sorts. There are no ulterior motives or big schemes, just a love of the craft and a place to be as crazy as I want to be.

V: How are your experiences working with B.CALM different than your experiences working with major or independent labels? Is it different from just releasing your stuff on SoundCloud?

FI: Well every label is different, but it’s a very different thing doing it all yourself. It’s fun, terrifying, difficult and exciting all at the same time. It provides a great satisfaction when things work out the way you wanted them to… but on the flip side there is also a horrible feeling of loneliness and fear when you need help and you turn around and realize you’re the only one there. But I am lucky to have an amazing wife and friends that help out wherever and whenever they can and ultimately I just have to realize it’s all for fun and the love of creating, otherwise what’s the point?

V: Your career has always highlighted your work ethic, and you’ve done a lot of do-it-yourself projects. What’s the draw in DIY for you?

FI: I don’t know, I’m a masochist probably. Haha. I guess I like getting my hands dirty. I have always been a fan of the do it yourself thing, ever since I was young. You start a band, you raid the copy shop, and you make do with the materials at your disposal. It’s inspiring, it teaches you problem solving skills and a good work ethic and ultimately, it means more. For me I enjoy the process…every step is important. The things I create are a part of me, and I like to be there every step of the way…falling all over myself. Fucking things up as I go along. My favorite parts end up being the mistakes.

V: Do you think DIY is important to the punk scene? Have you seen it grow in the community?

FI: I do, I think if it weren’t for the DIY ethics nothing would ever change. What you have to understand is, as disheartening as the thought may be, our world is run by business and all businesses have to make money. that means labels, distributors, publishers, hospitals, schools, government; you name it, it’s all about the bottom line. Yes, making ‘great art’ is wonderful and when ‘great art’ makes a profit everyone benefits and the world can change…(yes I believe great art can change the world). But if that ‘great art’ doesn’t sell, someone at the company is going to tell you and everyone else that your ‘art’ isn’t that ‘great’ and 99% of the time they will move on. It’s the nature of the beast, it’s not fair…but art and life seldom are.

Our creative world these days, especially the music industry, is set up to fail. We have a business that is losing money rapidly and the bossman is scared. ‘Don’t take any risks, play it safe, because we cannot afford to lose any more than we already are in this economy.’ So the same things are green lit over and over, more polished, more sexually explicit, dumb it down even more than last year, different packages of the same shit. Big money won’t take a chance on something new until it proves itself, because no one wants to be the guy or girl who lost their ass on some out of left field artist. But you see there is the problem..the only thing that can truly change the industry, or the world for that matter, is something truly new and inspiring. A hail Mary. Something so undeniably risky it ignites the world’s imagination. So, here we lie, dying in a vicious cycle. And this happens every 15-20 years or so.

DIY is where the revolution begins. Because greatness starts with being so goddamned crazy no one else in their right mind will help you, so you have to do it all by yourself. It’s how punk rock began, tattooing, street art, the fucking internet, you name it. Anything the mainstream has adopted, monetized, and bled dry over the years at one point in time started in someone’s basement. And that last statement sounds bleak as fuhk, I know, but it’s not all bad. Some amazing things have happened because of that. DIY has changed the psyche of the mainstream, of course it also means you have a billion or so dickbags wearing bedazzled tattoo flash on their jeans…but well you can’t win ‘em all I suppose.

V: DIY can mean a lot of things to different people – with B.CALM, you’ve released vinyls, whereas a lot of bands have taken to recording their music on their own and releasing it on sites like Bandcamp. What does DIY mean for you, as an artist?

FI: DIY to me just means doing it yourself on your own terms. I love the recording process. I enjoy it as much as I enjoy writing the songs and performing them… maybe even a bit more. And in today’s technological world it is a lot easier to have a home studio or a laptop and a microphone and be able to record a whole record in your bedroom. I for one feel blessed to be creating in a time where that is attainable. But that doesn’t mean you can’t record in an actual studio and still do it yourself, it’s all about the mindset and having your hands in the project at all times. The procedure of recording everything yourself allows you to make mistakes and learn from them. This will change you as an artist and as a player, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to all musicians at one point or another. I independently funded ‘for jamia…’ I created the art, I performed everything on it, recorded it and mixed it. I only turned the songs over to have them mastered and pressed. And when the records were returned to me I hand packaged, numbered and mailed all 400 to those who purchased them.

As far as releasing your material I believe that is up to the artist. No one should be able to tell you what to do with your art. If you want to put it up for free on a site like SoundCloud, as I’ve done in the past, or if you wanna put it on 8track and sell it through mail-order for a thousand bucks a song, that is your prerogative as the creator, and whatever you deem appropriate for you art is correct in my mind. DIY doesn’t have to mean give it away for cheap or free, that doesn’t change the do it yourself operation in my opinion, nor does the location of recording or sale.

I chose to press vinyl for my recent release because I have always wanted to release my own 45 and also because of the statement I feel vinyl has. For me I am a fan of the ritual. It takes more effort to put the vinyl on, and therefore demands more of you attention. I didn’t want ‘for jamia…’ to just be in the background, I wanted it to be an intimate conversation. I wanted the listener to be a part of it. You take the record out, lay it down, drop the needle and listen. Converse. Switch sides, hear a response, it should be an experience. Vinyl has more gravity than digital for me. However I am not oblivious to the world in which we live. I knew in order to have it reach more ears digital had to be widely available. But for me it was always about giving my wife the vinyl.

V: What effect does DIY have on the scene, given the recent trends of releasing music digitally?

FI: I think consumption of music digitally has really opened the doors and the reach for DIY artists. Before it was all about limited hand made releases, but now you have websites facilitating the worldwide distribution of independent artists, and I think that’s a great thing. Even though I have always been and will always be a fan of the artwork and packaging, I’m glad more independent artists will be able to see their work reach a wider audience. It’s much easier to fund your own batshit crazy projects these days, especially without the overhead of a physical release, and I think we’re going to see more and more artists doing what they want on their own.

V: It seems like DIY has become increasingly trendy – do you feel that it’s been commodified in any way? Do you think it will continue to grow as it has?

FI: I think DIY may be the new buzz word, but the trend of going back to basics in my opinion, is because of value. Doing it yourself brings the intimacy and care back to your art. Plus no one can tell you what to do, you’re your own boss, and that’s a special place to be as an artist. I’d like to think it’s also starting to make people realize there is a person and a soul behind the art and not just a product. But commodified? I don’t know. That seems to have a negative connotation, but I don’t think there is anything wrong with selling the things you create. Inventors and artists deserve to make a living and be paid well for what they do, I don’t see anything wrong with that.

People for some reason feel like if you’re able to download music easily or steal an artists whole discography in seconds that somehow you should, that it’s justified. That’s bullshit. The time taken to create and invent should be valued, respected, and revered…especially from independent artists.

Grant Morrison and Gerard Way provide insight on the great potential of the comic form, their creative relationship, and ‘the golden age of Australian superheroes’.

One is a New Jersey native whose band, My Chemical Romance, has packed stadiums for more than a decade. The other is a veteran comic-book writer from Glasgow, who has spent seven years giving voice to Batman. But Gerard Way and Grant Morrison have discovered they have a lot more in common than the surface suggests.

The pair will come together to present a show about comics, art, music and life for visual festival Graphic. An Australian premiere, the show is one of the drawcards of the four-day event, which also features Seth Green’s animated cult hit Robot Chicken Live and Pulitzer Prize-winning comic artist Art Spiegelman.

”It’s really exciting, because I rarely get to travel for anything other than music, so be able to go and not have heaps of bags of gear, and I get to sit and talk with my hero,” Way says.

A long-time fan of Morrison’s groundbreaking work – from the surreal insanity of The Invisibles to his legendary stint on Batman – the singer soon found it was a mutual appreciation society.

”I did an interview for Spin magazine and they were asking about my influences, so I talked about comics,” Way says.

”I talked about Grant’s work a great deal and he caught wind of that and reached out, as he was a fan of what I was doing. So, we had lunch – and I was obviously pretty nervous – but we’ve gotten really close. We also hit it off because we have a lot of things in common. We both do things very differently and we both do what we want to do.”

”I talked about Grant’s work a great deal and he caught wind of that and reached out, as he was a fan of what I was doing. So, we had lunch – and I was obviously pretty nervous – but we’ve gotten really close. We also hit it off because we have a lot of things in common. We both do things very differently and we both do what we want to do.”The 36-year-old has been passionate about comics from an early age, studied at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan and interned at DC’s famed graphic-novel house Vertigo.

”I spent one year at the visual arts school, where you do everything, then the next three years was studying everything from drawing to writing to colouring and inking – every aspect of a comic.”

But, playing music to be able to afford to work on his visual art, Way stumbled on to a 12-year career that would see his band sell nearly 4.5 million records, with four studio albums released, before their end in March this year.

”[The music] was purer than the comics I was working on; it wasn’t over-thought at all. It was just something that I did. But then, because I was so honest with the music, it took off. And I didn’t see that happening, because I wasn’t sitting there going, ‘I want to be this huge rock star.’ It was very, ‘I play music because I have to and I draw comics because I want to’.

”And the things I was trying to do, weren’t the things that took off.”

That was, until 2008 and the release of his acclaimed comic-book series The Umbrella Academy, which earned him and Brazilian illustrator Gabriel Ba an Eisner Award – the United States comic world’s equivalent to a Grammy.

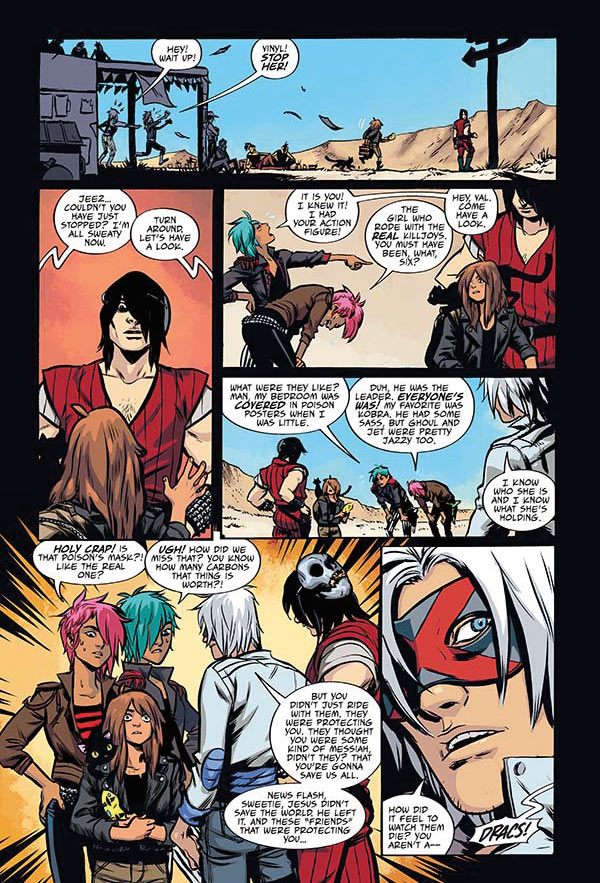

He is now working on a six-part series, The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys, currently four issues in. Band fans will recognise the name, with the final My Chemical Romance record Danger Days: The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys sharing the title and the Bladerunner-esque, post-apocalyptic setting of the album’s videos for Na Na Na (Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na) and Sing – on which Morrison worked, too.

But it was when good friend Shaun Simon revealed the comic on which he was working was remarkably similar to the one kicking around in Way’s mind that Fabulous Killjoys, the comic, found the momentum it needed – and a wonderful illustrator in Becky Cloonan to bring it to visual life.

”Shaun Simon had this comic he was working on about reality and it was called The Killjoys. I was working on a comic at the time and I didn’t have a title for it, but when he told me about his, ‘The True Lives of the Fabulous’ popped into my head,” he says.

”A week later I called him and was like, ‘Hey, I think we’re both kind of working on the same thing’,” he says. ”So we started working on this together.”

The series continues with a young girl rescued from the all-powerful, decidedly evil corporation Better Living Industries by anti-establishment freedom fighters the Fabulous Killjoys.

In a creative business such as the comic world, where male superheroes and stories dominate, it’s refreshing to celebrate strong, interesting female roles – something close to Way’s heart, as father to a young daughter, Bandit.

”A lot of it has to do with the kids I’d see in the audience [at My Chemical Romance shows]. A lot of them were these young women, very strong personalities, very independent and very creative, but also like they were trying to find their place in the world,” he says.

”That had a pretty big impact on me.”

When: October 4-7; Gerard Way and Grant Morrison are in conversation on Saturday, October 5, at 9pm.

Where: Sydney Opera House

Tickets: From $39 ($39-$59), sydneyoperahouse.com.

Show Former My Chemical Romance frontman and graphic novel writer Gerard Way joins iconic comic-book creator Grant Morrison to share stories of life, loves, inspirations and creative processes.

As issue two of The True Lives Of The Fabulous Killjoys is released, we thought it was time to catch up with author and My Chemical Romance frontman Gerard Way, as well as writer Shaun Simon and artist Becky Cloonan. This is part of a series of articles published to celebrate the ongoing Killjoys series, with the main interview in this month’s issue of Rock Sound, and the second part of this feature landing online on July 31.

Where does this release fit into the My Chemical Romance timeline?

Gerard: “The end of My Chem was the end. This was always intended to come out, maybe not the way it was originally written, but that’s just the case with everything. This is exactly what it was supposed to be. Anything in there that is relevant to the birth or ending of anything is not intentional. It’s the beginning of an awesome comic book career for Shaun, for Becky it’ll be a continuation of an awesome career. For me, it’s gonna be me stepping away from comics. So it’s beginnings and endings in a lot of ways.”

A lot of the story concerns teenage rebellion – Gerard and Shaun, as parents, are you prepared for your children to rebel no matter how good you are as fathers?

Gerard: “For fatherhood, there is nothing that can prepare you for it. Something that was very interesting during the record and even the life cycle of the band, was noticing the slight rebellion from the audience. A lot of these fans had grown up with us, so I watched them rebel against the world at large, and even against us in some way, and that was the point. None of that ever bothered me, because it made sense for them to rebel against us. Let’s say your enemy is boredom, corporate rock and people who don’t want to challenge things – you run the risk of becoming the enemy that you’ve taught everyone else to fight against. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel a little bit of that at times, but I think that is healthy and normal and you shouldn’t read into that in a negative way. I think it’s a fact of life that you become the very thing [you’re fighting], no matter what. Money and fame and all the things that make you what you are, and even if you try your hardest to hate that, you’re still going to possess some of those abilities and you are going to become a little less relatable. I felt a lot of teenage rebellion post and during ‘The Black Parade’.”

And you put a lot of that in the comic…

Shaun: “I think so. I’m worried about my kid growing up and not knowing what rock ‘n’ roll is. I’m in New Jersey and there is no rock [radio] station in New York anymore. Everything nowadays is so disposable, and it’s like listening to the same beat over and over again. I think a lot of that goes into this book. Teenage rebellion is a lot about diversity and another way of thinking, even what’s going on today in society. That’s what scares me.”

Becky, what was it like when you saw how extensively the spider had been used?

Becky: “Mind-blowing. Being involved from such an early point, from seeing the videos get made and hearing the album, it’s definitely made the comic as it is now. It’s perfected my art. I have so much more to draw on now; the videos have influenced the comic, or lyrics have made it in to the final incarnation of the comic. There are so many fans who make their own Killjoys costumes, and I think ‘That’s a cool mask, I’ll take that idea.’ There are so many people collaborating in a weird way.”

Shaun, what were you doing between being in a band and now?

Shaun: “I settled down, got married, had kids and became a barber. I’d always wanted to break into comics, though.”

Gerard: “One of the things he was doing was discovering comics – and I love the fact he discovered them late in life. There’s strength to that. He was only reading the good shit in a really dedicated way. I remember going over to his house after he had got married and his shelf was lined with the best books. He was passionate about it, his views were abstract and I felt like I really wanted to be a part of this next wave that he was a part of. Becky was the same type of artist. She’s in the small, awesome category where she is in a class of herself.”

For the second part of this conversation come back to the Rock Sound website next Wednesday, July 31. To read more about The True Lives Of The Fabulous Killjoys head to darkhorse.com.

As the former lead singer of glam punk heroes My Chemical Romance, Gerard Way knows how to tell a story. Concept albums Three Cheers for Sweet Revengeand The Black Parade unspooled bittersweet, goth-tinged tales of resurrected gunslingers and postmortem cavalcades into the band’s theatric thrash with style and substance. Way made the full transition to scripting with his 2007 Dark Horse comic The Umbrella Academy, the portrait of a dysfunctional family of superhero misfits searching for purpose while saving the world from mind-bending threats. A graduate of the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan and a former intern at DC’s Vertigo imprint, Way proved just as adept with a pen as a microphone, winning an Eisner Award in 2008 for Best Limited Series.

Today marks the debut of Way’s new series The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys, a heady descent into post-apocalyptic intrigue and grind house psychedelia that completes the story started in the 2010 MCR album Danger Days and its videos for singles “Na Na Na” and “Sing.” Along with co-writer Shaun Simon and artist Becky Cloonan, Way paints a conflicted world where a gang of teenage vagrants fights a totalitarian corporation and its legion of vampire-masked drones while a pair of android prostitutes shares a secret bond.

Over two interview phone sessions, Way chatted with Paste about his new comic’s connections to his past as a commercial recording artist and what inspired his aesthetic shift from white face paint to red hair dye. Way also digs deep into the underlying sociological issues at Killjoys’ heart and how Dora the Explorer, the Blade Runner documentary, and the Sega Master System influenced it.

Paste: Congratulations on your first issue of The Fabulous Lives of the Killjoys. This is a continuation of the story you started in your Danger Days album from My Chemical Romance. Did this plot emerge after you finished the album or was it a part of the story the whole time?

Gerard Way: The deal is that I had written three videos (“Na Na Na,” “Sing,” and “The Only Hope For Me Is You”), and the third video had never gotten made. By the time we had completed the second video, we just ran out of budget money. At the time, somebody was managing us and not keeping an eye on this stuff. Long story short, there was no budget. So I wrote a video, and of course it ends up being the most expensive one, as the last part would usually be. But we couldn’t make it!

Killjoys started its life as a very different comic. It was heavily-rooted in nineties Vertigo post-modernism. There’s a lot of very cool, abstract ideas in it; I wouldn’t even call it a superhero book. That (comic) was a visual and thematic inspiration on what would become the album Danger Days. It was pretty loose, though. This was going to be my interpretation of the story, so there’s way more science fiction involved. And what I need to say to the world needed to be a little more direct, so I boiled it down to something that’s still very smart and challenging, but I thought was definitely easier to understand through song or visual.

Then (Killjoys artist) Becky Cloonan drew a 7-inch for “The Only Hope For Me Is You,” which was going to be the last video single. I realized I was out of budget, so I said ‘just make this the girl from the first and second video at 15. And have her shave her head or chop her hair off like in The Legend of Billie Jean, because that’s how the video was supposed to start.’ So (Cloonan) sends this drawing over and I’m on tour with Blink 182 in a hotel on an off day. I get this drawing and I’m so immediately blown away by it. I call Shaun, my co-writer and co-creator, and I say ‘open your email, I’m going to send you something.’ I ask him ‘how does this image make you feel?’ We talked for two hours. By the end of the conversation we both realized that that image was the comic, and the third video was basically the comic. So we figured how we were going to make this interesting and exciting for six issues and complete the story. And that was the final direction. It was pretty obvious to us.

And I like the fact that the story was about The Girl. It’s basically about somebody who was selected for this higher purpose who simply didn’t want to do it.

Paste: This story arc dates back to around 2009, which is when your daughter, Bandit, was born. Does Bandit inform the character of The Girl at all?

Way: (Co-writer) Shaun Simon was the first of our friends to have a child, and it was really crazy to even think of that. And then when (Way’s wife and Mindless Self Indulgence bassist) Lindsey and I had Bandit, I got it. And that’s when Killjoys really started to click. And I do see my daughter in her, because, for better or worse, she’s going to be her own person when she grows up. She’s going to be amazing, obviously, and have her own dreams. I just think there are going to be occasions where there’s this kind of weirdness based on what her parents used to do for a living. I think there’s an element of that even in the comic where The Girl used to hang out with these dudes who were shot, and people have different opinions of them. Some people like them, some people hate them. She has to deal with that. That’s the cool thing. You don’t get to see that stuff in comics.

Paste: One interesting element of the issue is the Draculoid masks, which force the wearer to experience an artificial perception of fear and victimization shared by all other Draculoids. It all feels vaguely political, reminding me of when Glenn Beck attacked your song “Sing” as propaganda after it appeared onGlee (there’s also a scene where the Draculoids complain about loud music). The main irony is that the masks came before Beck attacked you. Were you reacting to anything specifically when you first created the masks?

Way: (MCR guitarist) Frank Iero had that mask. It was just an aesthetic thing. ‘70s horror masks are pretty incredible. There’s something that’s really amazing about that era of painted rubber and hair. It kind of represents the past of the band. I liked the idea of them now becoming our enemies, just chasing us down or haunting us. All the Glenn Beck stuff, that came from a place of being in a rock band that started literally playing in basements. Even when we got big, it still felt like that same band playing in basements.

This isn’t even a jab at the record label, but when you have a large success like The Black Parade, the stakes really get high and a lot of people rely on your success, even magazines. You’re just part of this industry that feeds on a monetary exchange, which is fine — I’m not bagging that. So you’re expected to transform into this thing that’s a rock band. ’It’s cool that you’re like this, but now we just need you guys to be a rock band, and you need to become stable and we need to know what to expect from you.’ That kind of pressure can really mess with your art and really mess with your head.

So the whole Better Living Industries thing is about being part of the solution and part of the problem. Are the Killjoys the heroes? If you want to look at it in a nihilistic 15-year-old point of view, watching A Clockwork Orange for the first time, I guess you could see them as the heroes. Are Better Living Industries (BLI) really the bad guys? Who’s the bad guy? I feel like The Girl just wants to hang out with her cat.

Paste: So The Killjoys aren’t necessarily the heroes and Better Living Industries aren’t necessarily the villains; this comic is more grey. It reminds me of The My Chemical Romance song “Teenagers,” but these teenagers are a bit crazy and Clockwork Orange-ish.

Way: To bring it into A Clockwork Orange, I think I saw that when I was way too young. I had a couple of really cool friends when I was a kid, and we’d find cool music and movies and show them to each other. My friend Dennis had a copy of A Clockwork Orange and he’d already seen it once, and he was like ‘we need to watch this.’ I was sleeping over his house — and I think we were literally 15 — and we watched it. I remember my first reaction to that film was very similar to my reaction to Taxi Driver or my first reaction to Watchmen, where you just immediately gravitate toward Rorschach in Watchmen or Alex fromClockwork. And then you start to get older and realize that character wasn’t a hero at all; they’re really bad people who didn’t do anything heroic.

When you’re exposed to that as a youth, you misconstrue stuff. Sometimes you literally only take it on the surface, and you see any strong action that’s done with conviction as the right action, and you start to realize later on in life that just because you felt strongly about it, it doesn’t mean it was the right thing to do. And that’s one of my feelings that I tried to inject into The Killjoys, especially with the characters of The Ultra-Vs. (Shaun and I said) ’let’s literally make these characters 15-year-olds watching A Clockwork Orange, just pulling all the wrong shit from it.’

Paste: Are there any modern-day equivalents of Better Living Industries?

Way: In a lot of ways I feel that BLI wasn’t based on any specific corporation, it was just based on us. I felt that’s also what you could become: if you start off as a 15-year-old watching A Clockwork Orange and go to that extreme so young, you could become the person in the white office saying what’s right and wrong, saying what people should and shouldn’t do, making sure everything’s very clean. Those two types of people are literally the same person, they’re just at different extremes. I just based Better Living Industries on us as people. Whether we realize it or not, a large amount of us likes things to be organized, structured, clean, cleaned-up. That’s what we like, that’s what we go for.

Children’s programming for the most part, not all of it, is literally children coming out of some sort of camp or mill. And that’s not a hyper, aggro punk view on it, that’s just a fact. And so not only is that happening, but kids are responding to that. And parents are totally comfortable with the kids watching that. There’s nothing really wrong with that, but it says a lot about who we are. As free and crazy as we want to be, and how much we want to make the world a canvas, there’s also a part of us that doesn’t want to make any mark.

Paste: Did you notice this from watching what Bandit watches? How do you deal with this as a parent?

Way: I noticed it when I finally got to see a show like Yo Gabba Gabba!, and I realized there was such a high contrast in children’s programming between a show that people are taking a risk on and really trying as opposed to a show they know is just going to work. I didn’t realize at that point that there was such a high contrast in that kind of artistry. Flat out, Dora the Explorer…I don’t care if the people who made it are nice people, there is zero artistry that goes into that. There’s also, I believe, zero reference to the real world. I don’t even think images are Googled to have them correctly drawn. You’ve got that, then you’ve got Yo Gabba Gabba!. I know I’m friends with those dudes, but the reasons I became friends with them was because I admired their work. The people really try, so I notice that a lot. There’s a lot of bad stuff, there’s some good stuff. You just have to dig it out.

Paste: Talking about the general aesthetic of the comic and the Danger Days album, there’s a huge difference between the art direction of The Black Parade and Killjoys as both a comic and album, and it was mirrored sonically in the music as well. Was there anything that jumpstarted the bright, jarring color scheme and the garagey sound?

Way: As a musical starting point, (Danger Days) was protopunk and garage rock. So it started with The Stooges and then I put it through a science fiction lens. I went on this musical journey where, if this started with The Stooges, it ended with The Chemical Brothers. I remember listening to Exit Planet Dustwhen I was 14. That record, more than a lot of punk records, made me want to get up an run away from home. A lot of the digital came from that. I know EDM was happening at that time when we were making (the album), but it was still very underground. People weren’t winning Grammys for it yet, and it wasn’t on the radio. Right at that moment we were making Danger Days and we were a year and a half ahead of EDMexploding. The kids are getting their energy from machine-made things, not human beings playing through the same gear as the last band. That’s where that also came from sonically; I thought that was going to be the best idea to communicate.

Paste: You cast Grant Morrison as the villain Korse in your videos for “Na Na Na” and “Sing,” and he also survived into the comic. Some of the visuals remind me of The Invisibles as well. Did Morrison have a hand in the story at all?

Way: Well, he did and he didn’t. He did in the sense that to me and Shaun, (Morrison) was our biggest inspiration and our influence. It’s as if Shaun and I were in a band together and we loved Queen. We love ‘90s Vertigo. To us, if we had to pick a favorite from that (era), it would be The Invisibles. So in that way, Grant had a giant hand in it. There were also really cool collaborations that would happen when I was doing wardrobe designs and would sit with Grant. I’d already made his weapon at that point, so I handed him his gun and asked ‘how do you see this guy?’ or ’what’s in your subconscious that you want to come to the surface? Who is Korse?’ He immediately, because he’s Grant, had a vision for how he wanted to look. He said ‘I think he should be a bit of a dandy,’ which I had never thought of at that time. That made me think of Edward James Olmos’ character (Gaff) in Blade Runner. This guy’s a bit fancy, and he grooms himself very well. Grant even had all this crazy backstory for Korse that was really awesome. Spiritually and emotionally, artistically — more so in a guidance sense — (Morrison) was very, very hands-on with it.

Paste: I know you’ve cited Mad Max and The Warriors as influences, but I also saw some parallels to anime like Akira. Did that play a conscious hand?

Way: Absolutely. I was at a convention in New Jersey, and this was when conventions were still small; it was in a small area of a local hotel, like a Hilton. I walked past this TV, and this guy had a ton of VHSs, and I looked at this animation that was gorgeous. It wasn’t rotoscoped, and it also wasn’t like Voltron. I had read Akira as a comic, and had heard about them making it into a movie, but back then you got your news from the back of the issue you were reading. I knew exactly what that video was when I saw it, because one of the gang had just been beaten up by a Clown, so he was vomiting blood. I would never forget that shot. I bought it immediately. I spent all of my money on just that. I just went home with aVHS that I played every day. Constantly.

Having been a huge fan of the comic, too, there’s a lot I took from it. There’s a total reason the back of my jacket looks like Kaneda’s. But it was always important to me, even if I was reappropriating, to push myself design-wise to say, ‘well I like Kaneda’s pill, but how do I one-up it?’ That’s my challenge for the day. How do I make this different or a little more interesting? I turned it into this weird, graphic skull by adding crossbars under it to really make it a poisonous thing. Akira was huge. The Trans-Am to me is basically Kaneda’s bike. If I didn’t have red hair, I’m sure I would have been wearing red.

Paste: Did you ever play the videogame Jet Set Radio Future?

Way: In terms of having an influence on me, that came out a little late. But there was a game called Zillionthat was out for my Sega Master System, and that was a little impactful too, like Phantasy Star II for Genesis. There was some interesting stuff that threw its hat on the ring on this project.

Paste: What’s the most obscure or esoteric influence?

Way: There’s a film called Mr. Freedom by a French director who’s pretty bananas, literally about American superhero violence. Blade Runner wasn’t as much an influence as the documentary about the making of it. That had a bigger impact on the entire project. Watching the interviews, (director) Ridley Scott spoke about how challenging it was to get what he wanted, and how many problems it caused and how many bridges it burnt. Just what a struggle it was to have his vision seen through. I guess I really identified with that. There’s a quote from him where he references his camera as a weapon. I’d never heard a director do that and I started to see my art that way and see music that way. So that was actually the biggest influence, this documentary.

Paste: What do you want people to walk away with after reading this 6-issue miniseries?

Way: I think the main thing I want them to walk away with is a deeper understanding of the artistic process. I would love it if they walked way from it, despite it having some stereotypical trappings of science fiction and dystopian society, getting something new out of that. We’ve all gotten amazing things from Ray Bradbury and Logan’s Run. I just don’t think we’ve ever gotten the other side of that. We know that it’s bad to be a Sandman shooting people because they’ve turned 21; we don’t ever get to sympathize with why they do it. There’s a bit of sympathy for the devil in this, especially if people take away that we’re all kind of the devil in a weird way. We all have a hand in promoting safe culture. It’s easy to say ’he’s such a bad guy,’ but would I have done the same thing? There’s a lot more sentiment in this than there is in The Umbrella Academy and there’s also a lot more nostalgia. I just want them to get something different from science fiction in this.

Paste: You’ve also been tweeting some incredibly original Batman art from a 2008 pitch. Is there a reason for releasing it now?

Way: I guess it all comes back to that essay that I wrote when the band ended, where I intended to be completely obtuse and secretive when the band was existing, and when it stopped existing there was no need for secrets any more. So I started applying that to all aspects of my life. I was cleaning my office and I ran across what I felt were these really cool designs of Batman that I was proud of. I’m sitting there going ‘what if this never comes out? Why am I going to keep this in a box?’ I started to feel that way about a lot of stuff. What’s the worse that happens? Eventually the book gets made or it doesn’t get made because I released stuff. As it is now, I don’t have time to write it, so I don’t see that happening in the future. I stopped being so precious. I stopped being so greedy with my art. In a weird way, it’s this greed based in fear, and I have boxes of stuff that nobody’s ever seen that I keep to myself. Some of it I obviously should — not everything’s for sharing. I stopped being precious with everything, and I’m applying that to my life and the music that I make and the comics that I make. I don’t believe anymore in the hype machine or the strategy. I believe that you make something and then you share it. There’s no reason to wait.

Via